“The German Chain That’s Beating Wal-Mart at Its Own Game” says Bloomberg about Aldi in this article from March 22nd. This is my last Spring Break’s post, sent from the friendly, and beautiful Charleston, SC. A special thank to Louis, a regular reader of HowToGuide, who sent me the link.

The German Chain That’s Beating Wal-Mart at Its Own Game

In the Southern California town of Beaumont, Wal-Mart shoppers must first drive past the new Aldi, a recent addition to the family-owned German grocery-store chain that is beating the U.S. retail giant at its own game: selling food at rock-bottom prices.

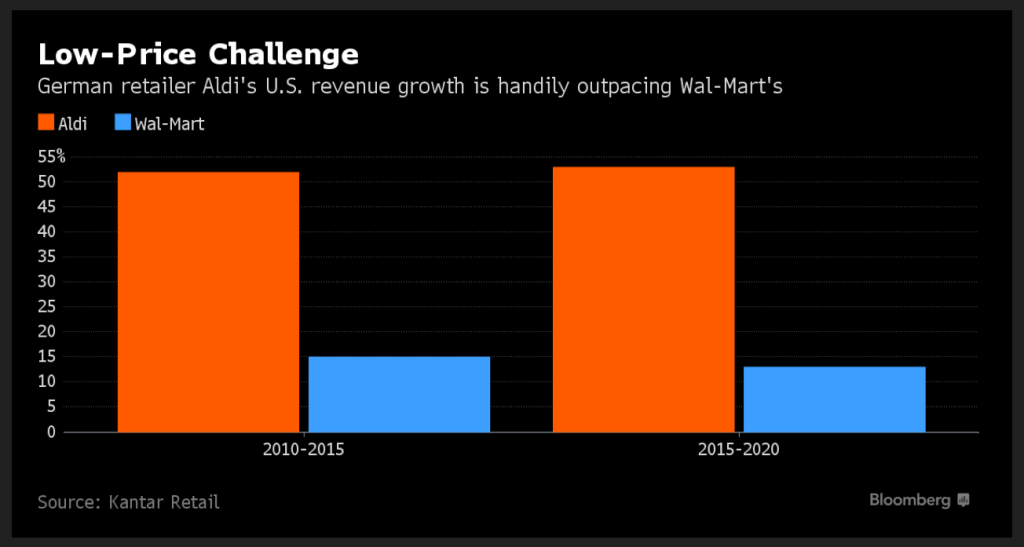

Aldi is betting that many in Beaumont will never make it to the Wal-Mart. Like hundreds of others Aldi has opened in recent years, the Beaumont store is strategically located to siphon off the retail giant’s discount-seeking shoppers with prices that can average almost 20 percent less than those at Wal-Mart Stores Inc.

Aldi stores lack the massive size and selection of a Wal-Mart — they tend to be around one-tenth the size of an average Wal-Mart and carry few national brands. Yet their rapid proliferation and the chain’s ability to offer even lower prices than Wal-Mart are putting pressure on the Bentonville, Arkansas-based discounter. And as Aldi expands aggressively in the U.S., it’s becoming just the latest in a long list of problems for Wal-Mart.

“It’s like a thousand cuts,” said Leon Nicholas, a senior vice president at consulting firm Kantar Retail. “They are impacted by Aldi, by Amazon, by the dollar stores — and all these things add up for Wal-Mart.”

Under Pressure

Wal-Mart, whose shares have declined 19 percent over the past year, isn’t the only grocer under pressure by competition from Aldi and regional chains like Kroger. Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co., which operates under brands including A&P and Food Emporium, filed for bankruptcy last year, just three years after emerging from court protection. And Fairway Group Holdings Corp. may be on the brink of default this year as it struggles to expand in the New York market. Both are battling competition on the low end from discounters like Aldi and, on the high end, from retailers like Whole Foods.

Wal-Mart, with $298 billion in annual U.S. revenue from its 3,500 superstores, is on far more solid financial footing. But with more than half of that revenue coming from grocery sales, it can scarcely afford to lose customers to Aldi, which is going after the same discount-minded lower-to-middle-income shoppers. Sales at U.S. stores open more than a year rose just 0.6 percent last quarter. The discounter is spending $1.5 billion on higher wages this year, raising minimum pay to $10 an hour. That, together with investments to improve its e-commerce offerings, could sharply crimp profits this year, the company has said.

Major Expansion

At the same time, Essen, Germany-based Aldi has quietly grown its U.S. business to nearly $13 billion, according to Kantar data. A closely held company focused mainly on the East Coast and Midwest, Aldi doesn’t disclose its sales or profit. But Kantar forecasts that within five years the company’s annual sales will reach nearly $20 billion as total stores increase by about 33 percent to 2,000, including a major expansion on the West Coast.

Wal-Mart executives say they have a plan to punch back. Chief Executive Officer Doug McMillon has been cutting costs over the past year, including eliminating jobs, closing underperforming stores and negotiating new contracts with suppliers. He’s also said he plans to lower prices further this year even as Wal-Mart improves the quality of its fresh foods and speeds checkout times. And it’s experimenting with shopper innovations such as expanding an online grocery service where customers can buy their food online and pick it up without leaving their cars.

Pasta Sauce

Wal-Mart’s ongoing challenge, though, is that its longtime marketing mantra of “everyday low price” is no longer resonating for shoppers going to Aldi in search of bargains. In a suburb of Detroit, Aldi’s in-house brand of pasta sauce was 50 percent less than Wal-Mart’s store brand, its pancake syrup was 20 percent less, and its black beans sold for 18 percent of Wal-Mart’s. Some fresh foods also sold for less, with avocados and ground sirloin about half the price of Wal-Mart’s — though Wal-Mart had better prices on onions and chicken breasts. A pricing survey in July by Bloomberg Intelligence found Aldi items averaged about 19 percent less than the comparable Wal-Mart items sold in the New Jersey area.

“The company has really given up its price leadership,” said Scott Mushkin, a senior retail analyst with Wolfe Research. “We are a far cry from when Wal-Mart would have had a 15 percent discount to the rest of the market.”

Spartan Presentation

Aldi’s level of frugality can make Wal-Mart look downright extravagant. Its stores run on as few as three to five employees at one time, made possible because of its limited selection of items and spartan presentation. No opportunity for cost savings goes unnoticed. The chain eliminated the need to pay employees to fetch carts in the parking lot by making customers pay a 25-cent deposit per cart, refundable upon returning the cart inside the store. It also charges for bags and only recently started taking credit cards. And Aldi doesn’t focus on national brands, such as Oreos or Frosted Flakes. More than 90 percent of its products are lower-cost versions of the household names.

“It has really chipped away at Wal-Mart’s everyday low price image,” said Nicholas. “Wal-Mart is definitely concerned about Aldi.”

This article from Bloomberg originally appeared online on March 22nd, 2016

Foto credit by alphaspirit

Having lived in Germany for 9 years and shopped regularly at Aldi, I would have bet the farm they could not make it in the U.S. I was never more wrong.

I read in the papers this week that Aldi engaged in a cooperation with Jette Joop. I don’t know if you remember but she is a quite famous fashion designer in Germany. Here is the link to the full Handelsblatt’s article http://www.handelsblatt.com/unternehmen/handel-konsumgueter/aldi-sued-kunden-reissen-sich-um-jette-joop-mode/13430372.html

This is a super interesting development in the retail world. We now have a brand-new Aldi too in Eden Prairie, very close to Walmart, Target and Costco. And not far from a Trader Joe’s that we just love…

Here is another cool topic for you: why are the Germans (Aldi, Trader Joe’s, Lidl) succeed in America, where the French (Carrefour, Auchan, Leclerc, etc.) did not? I always thought the French were the champions in low-margin retailing, but I may be mistaken. What are your thoughts/theories about that?

Hélas non, les marges de la distribution en France sont bien supérieures à l’Allemagne, j’assume donc que les Etats-Unis marchent aussi avec des petites marges (je vais me renseigner). Aucune chaine française n’a marché en Allemagne : les Allemands n’ont jamais été prêts à payer plus pour plus de choix.

Finalement c’est Rewe qui se rapproche de plus en plus des concepts français… Large gamme allant jusqu’au haut de gamme, spécialités à fortes valeurs ajoutées etc. leur secret ? Un PDG français, Alain Caparosse, un sacré bonhomme !

Very interesting and well researched article.

On price comparisons, I was wondering if Aldi has a national pricing or not. That might explain why differences may exist with Walmart where it would be surprising that prices are nationally aligned.

Also I find a major difference between the two stores may be the much higher product turnover per line item including for the seasonal offering of non grocery products at Aldi, which make warehousing cost probably negligible compared to that of Walmart.

Indeed, a well researched article from Bloomberg.

Here is my secret: I read The Economist, and Bloomberg for the American side, Der SPIEGEL, and Handelsblatt for a German view, and eventually Les Echos for the French opinion.