Brexit, Trump, French Primaries—the Pollsters Were Wrong. Is Google the Future?

After Scotland, Brexit, Trump, and now France’s primary, pollsters in many countries have been wrong in predicting election results. A politician might say that the only poll that matters is the one on Election Day. However, as an interested world-citizen, I can’t wait for a collective mea culpa and, more importantly, an in-depth correction of their polling methodology. Meanwhile, Google gives better electoral predictions.

On November 8th, CNN published an article entitled “Could Polls Be Wrong?“. As we know now, they were not only wrong about the primary, but also the presidential election. This is not only an American problem. The United Kingdom and France are two more examples how pollsters got it all wrong during the last year.

In the UK, polls got the last two British votes wrong, with Brexit being the most famous. Last June, the average of opinion polls showed a lead for remaining in the European Union with 51-52%. Brexit won with 51.9%.

In the USA, even after the FBI announcement shortly before Election Day, Clinton was up by three points in a CNN poll. She won the popular vote, but lost the election.

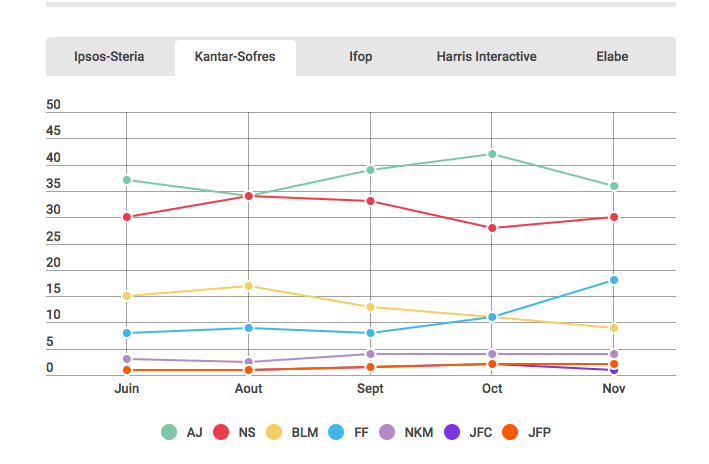

Last Sunday in France, favorite Alain Juppé lost the French Republican primary severely to an outsider. The polls were completely wrong.

Why are pollsters wrong?

The reasons for these faulty polls vary from country to country. In the United Kingdom, polls have failed to include people who normally don’t vote but voted leave. In the United States, the country is so large that it’s not easy to get a representative sample of the voting population. In France, it was the first time that French people were called to a US-style primary.

I assume that the nature of the elections in the UK and United States also may have messed up the pollsters’ models. Some Trump supporters maybe felt embarrassed to back a candidate who openly supports racism and xenophobia.

However, this discrepancy is nothing new. A concept called the Bradley effect describes the phenomenon of people being more likely to give socially acceptable answers when asked over the phone.

In 1982, African-American Tom Bradley was candidate for governor in California. Most polls predicted he would win, but he eventually lost to his white opponent Deukmejian. According to Wikipedia, post-election research indicated that a smaller percentage of white voters actually voted for Bradley than polls had predicted, and that previously undecided voters had voted for Deukmejian in statistically anomalous numbers.

I’m sick and tired of wrong polls

I’m fed up with false predictions. Pollsters, you get paid for this job, so check your population sample, undecided voters, and biases. Google challenges you silently on this topic!

I’m also annoyed that newspapers rely on poll results. Dear journalists, you should know better; you’re the investigators! You’ve heard of Brexit and the unexpected results. You saw that the primary polls were far from perfect. Why did you lull us into such uncritical thinking?

Most of all, I’m mad at myself for having forgotten my healthy suspicion. I remembered the wrong primary polls of the past. I remembered the wrong Brexit polls. I saw the Republican Eastern Shore during the summer. Then, I just enjoyed polls that were saying what I hoped was right.

(I wrote a post in French the day after election with the same topic: J’accuse journaux et sondeurs)

Pollsters are wrong. Is Google the future?

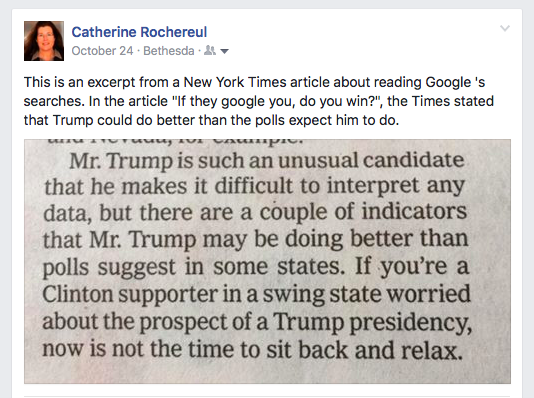

On October 24th, I posted on Facebook an excerpt from a New York Times article about how hard it is “to interpret any data.”

The newspaper wasn’t talking about polls but how Google searches could be used to predict events.

In primary elections, Google search volume for a candidate in a state has predicted electoral outcomes. It is also true that in each of the past three general elections, the candidate with the most Google searches . . . received the most votes. This time around, nationwide, for every Google search about Hillary Clinton, there are two for Mr. Trump.

The New York Times doubted the outcome and had funded arguments to justify its position. You can read more here: “If They Google You, Do You Win?”

However, based on Google searches, the Times predicted a drop in African-American turnout:

The main insight from Google searches this year is that African-American turnout may be down in 2016. There are significantly fewer searches for voting information in cities with large black populations than there were in 2012 and 2008. This suggests that even though African-Americans overwhelmingly disapprove of Mr. Trump, they will turn out at lower rates.

Other data suggesting a Trump win is a little more tricky: the order in which the candidates appear. How? Many searches contain both candidates’ names, like Trump-Clinton polls or Clinton-Trump debate. The New York Times suggests that a person is “significantly more likely to put the candidate they support first in a search that includes both names. . . . In the last three elections, the candidate who appeared first in more searches received the most votes.”

In April 2016, a French website published a similar analysis concerning the last elections in France, the UK, and Canada.

I’m pretty sure that in Mountain View, California, many Google executives and analysts are working hard to produce more data. But this raises a completely different question: is Google still a search engine or the Big Brother described in George Orwell’s 1984?